Take steps now to eliminate confusion, stress later

By Barbara Pierce

Talking about dying doesn’t lead to death. Yet most of us don’t want to talk about it.

Though most of us agree that talking with our loved ones about how we want to die is important, few of us do.

This concerns Kevin B. Mathews, a physician with the Mohawk Valley Health System who is board-certified in family practice and hospice and palliative medicine.

“If you knew you had a serious illness and your time is short, what matters to you? Would you want more medical treatment? Or would you want to be with your family at home or in hospice care? It’s important to begin to think about this,” said Mathews, who is part of the MVHS palliative care and integrative medicine program.

“Look into it, then discuss it with your family and your physician. Don’t wait until you’re in the ICU or a nursing home,” he said.

Yet that is likely to be our fate. Though most of us say we wish to die at home, the reality is that most die in a hospital or nursing home.

“Surrounded by teams of doctors and nurses, respiratory therapists and countless other health care providers pounding on their chests, breaking their ribs, burrowing IV lines into burned-out veins and plunging tubes into bleeding airways,” is how emergency physician Louis Profeta describes this experience online in “I Know You Love Me — Now Let Me Die.”

“Now we can breathe for her (a terminally ill old woman), eat for her and even pee for her,” continues Profeta. “Then she can be placed in a nursing home and penned in a cage of bed rails and soft restraints, fed Ensure through a tube into her stomach and kept alive … ”

If this doesn’t sound like the way you would like to spend your last days, thinking ahead is the answer. So make sure the people who are likely to be making treatment decisions for you at the end of your life, including doctors and family members, know your wishes.

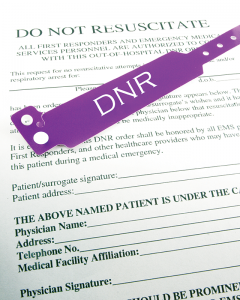

“Advance planning is the general term for this,” said Mathews. “Having a health care proxy is the first step.

“If you can’t make decisions about your medical care for yourself, your health care proxy makes them for you. They make decisions for you, provided two physicians concur that you are unable to make decisions for yourself. Your proxy is legally bound to follow your wishes.”

This person should be someone you trust; it doesn’t have to be your spouse or a close relative,” he noted.

“If you don’t have a proxy, a third person makes the decisions. That person is not legally responsible to make the decisions you have identified but makes decisions they believe are in your best interests,” Mathews said. “Everyone over 18 should have a health care proxy.”

Forms to appoint a health care proxy are available online. Mathews recommends the one found under medical orders for life-sustaining treatment on the New York State Department of Health website.

The next step is to let your health care proxy know your wishes. “If you haven’t spelled out what you want, to make these decisions for another person puts one under a great deal of stress,” added Mathews.

If your time is short, how much medical treatment do you want to endure if it means you might be unconscious or on a breathing machine?” asks Mathews. “These answers will change, depending on your age and what you have already gone through. For example, there comes time for a patient with cancer where more treatment doesn’t improve the quality of his life or lengthen his life.”

Honest communication with your family and health care proxy will help them avoid the stress of guessing what you would want. Muster up the courage to bring up the subject before accidents, illness or infirmity make decision-making more difficult.

If you make these decisions in advance, the stress on your family is considerably less. One study found that when a family member died in the ICU, the family suffered serious emotional consequences after the death, symptoms like PTSD, added Mathews.

National Healthcare Decisions Day in April encouraged conversations about advance planning. As these conversations can be difficult to begin, suggestions can be found on its website (www.nhdd.org/) by clicking “Conversation starter kit.”

Having a conversation with your direct primary care physician is most important also, added Mathews. “You need honest information about your condition as your illness gets more complicated and you get older,” he said.

These discussions are critical— so much so that Medicare now reimburses physicians for advance care planning conversations with patients.

The next step is to put it in writing in a living will, which is technically not a will but a legal document. Also called a directive to physicians or advance directive, it lets you state your wishes for end-of-life medical care. Your living will should be placed together with your health care proxy.

To begin thinking about end of life decisions, there are good resources online Mathews recommends:

— www.compassionandsupport.org/ is pertinent to New York state.

— The National Institute on Aging has several good publications. Go to: nia.nih.gov/, click on publications, then end of life. Also, Google “Caring conversations — Center for Practical Bioethics.”

By accepting that we know we will die someday, we can then make the decisions that pave the way for the peaceful death most of us want.